Community engaged journalism is a process that begins with listening, and involves intentional and repeated outreach to communities. This approach pushes us to challenge dominant narratives about communities, as well as our own biases and assumptions.

But, we can’t do any of that without a good foundation for understanding and committing to diversity, equity and inclusion in our newsrooms and in our coverage.

The summer of 2020 turned up the heat, but this has been an ongoing issue for public media, and all media. In a DEI training from the Maynard Institute for America Amplified collaborators last fall, Co-Executive Director Martin Reynolds said, “If we’re not rethinking everything about how we’re covering this moment, it will be like every other time before.”

That goes for all of our coverage, not just the stories we tell about protests against systemic racism and police brutality. This means we need to foster a culture of critique in our newsrooms.

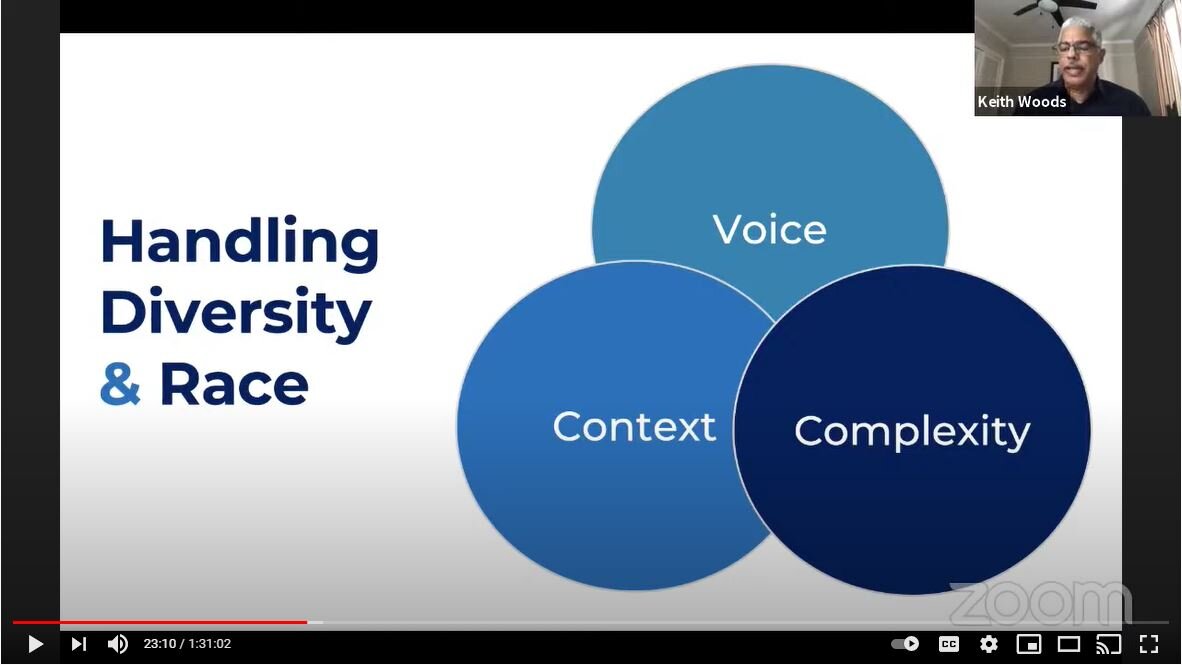

Something NPR’s Chief Diversity Officer Keith Woods knows all about. We partnered with him recently to take a closer look at a few stories from our America Amplified reporters through the lens of race and ethnicity.

Here are some key takeaways:

“Get out of the way as much as possible” in the story

“In stories that are about generally underrepresented or misrepresented groups, when we don’t have voice[s] [from the community], we wind up talking about people and not for them, and certainly not with them. That disenfranchise[s] people. You risk mischaracterizing them, and depriving your audience of a greater truth,” Woods said.

St. Louis Public Radio reporter Chad Davis says keeping in touch and following up with sources makes a big difference: “Just having an open conversation with them and telling them how the discussion is going to go into the story, in the first place, I think really helps out,” he said.

So, break out of interpretation mode, don’t paraphrase, and make space for much needed emotion and complexity in the story.

Listen for the unexpected

Move the listener beyond stereotypes and archetypes by exploring complicated truths in the story.

“The only way you do that is to keep listening to people until you’ve gotten past the thing you expected to hear,” Woods said.

Remember: “Facts without context distort the truth”

“When we leave the audience to fill in the blanks, we are leaving our audience at the mercy of stereotypes, biases, bigotry. And the more the group is underrepresented or misrepresented, the more likely that is. So, where leaving out context in any story weakens it, leaving it out in this case does active harm,” Woods said.

It’s on us to give our listeners direction, and intentionally connect the dots to teach and point our audience toward the truth.

Exercise a more rigorous examination of the why when it comes to identifying sources by race and ethnicity

Nebraska-based freelance reporter Megan Feeney grappled with this in a story that touched on whether shifting demographics could play a role in the electoral vote from Nebraska’s second congressional district.

“The thing I struggle with is this idea that whenever we identify race in a story, it [feels like] the de facto race is [assumed to be] white,” she said.

Woods cautioned: “When we drop a racial identifier into the story, we’re signaling to the audience that race is influencing what you are about to hear. We have to recognize that with the inclusion of race, we are making a connection that the story needs to back up.”

That’s why we need to more rigorously ask ourselves “why?” when including a source’s race or ethnicity. Otherwise, Woods said, we’ll end up leaving the listener to draw their own conclusions.

Avoid drawing equivalence between opinion and expertise

The false equivalence between one person’s opinion and another’s expertise is an imbalance Woods said he sees a lot in reporting and writing about race. This is not only disrespectful to the person who has the expertise, it is also a disservice to the bigger picture, the audience, the community.

Mountain West News Bureau reporter Nate Hegyi dealt with this in a story he produced four years ago about redface and appropriation of Native American culture in a float in a Montana high school parade.

“It smacks of both side-ism without context, and it’s not how I would approach the story today. I would’ve included the voice of an Indigenous scholar to point out how these kinds of parades perpetuate racism in the American West,” Hegyi said.

Avoid codes and euphemisms

Woods said to watch out for codes not only in our sources’ language but also our own. An example is in immigration conflation — where we conflate Latinos with undocumented immigrants.

“We are communicating outside of ourselves. And I might know what I mean by this phrase, but I’m not sure that once it leaves my mouth and comes to your ears, it means the same thing,” he said.

A few years ago, KCUR community engagement reporter Laura Ziegler reported on growing tension over the presence of Latino community members in Belton, Missouri, after the topic repeatedly arose in listening sessions and in social media outreach.

“It was very hard, as these stories tend to be, to get anything but a super nuanced idea about what that felt like and looked like. And I don’t feel like the voices that I had really adequately represented that,” Ziegler said.

Of the story, Woods said, “people of color are identified because they are the ones experiencing bigotry, but the actions on the other side are explained in terms of age, income, political leanings, tenure in a community there’s this long list of things that people will name before racism.”

Woods offered this advice: name whiteness. Don’t let it be the unspoken, assumed antagonist.